Saturday, March 30, 2024

Foie gras (9) Adipocyte ROS

Sunday, March 24, 2024

Foie Gras (8) Vaughan's macrophages

Foie Gras (7) What do you mean by inflammation?

Animal Models of Inflammation for Screening of Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Implications for the Discovery and Development of Phytopharmaceuticals

BTW MPO is the myeloperoxidase we've seen recently in Vaughan's paper. HOCl is bleach, it's an inflammatory tool. We use it to kill germs.

So this lets us redraw this doodle of inflammation with a small modification:

Right up at the top of the inflammation doodle is a small red circle labelled PLA2, phospholipase A2. Its job, in the event of tissue injury, signalled by ROS and derivatives, is to release arachidonic acid from lipid membranes which then allows the generation of a raft of inflammatory mediators using cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase enzymes.

Tuesday, March 19, 2024

Foie Gras (6) inflammatory mRNAs

Okay, time to look at this study

Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1)

Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 (MIP-1)

Monday, March 18, 2024

Foie Gras (5) An aside on how to stay slim

Another one-liner:

Foie Gras (4) RER

Fat Quality Influences the Obesogenic Effect of High Fat Diets

Foie Gras (3) The Japanese mice

Fat Quality Influences the Obesogenic Effect of High Fat Diets

If we imagine the Italian rats had been offered ad-lib access to the safflower/linseed diet we could expect them to eat somewhere in the region of 380kJ x 135%, so around 500-530kJ/d.

Saturday, March 16, 2024

Foie Gras (2) Lard fed rats

Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans

which provides this gem. These are the *daily* caloric intakes of rats on bog standard lab chow, in grey, or during the sudden onset of feeding lard based D12492, in black:

"Rats were divided in two groups with the same mean body weight (250 ± 5 g) and were pair fed with 380 kJ [90kcal] metabolisable energy (ME)/day (corresponding to the spontaneous energy intake of the same rats, that was assessed [on chow] before the start of the experiment) of a lard-based (L) or safflower-linseed oil based (S) diet for two weeks."

An isocaloric moderately high-fat diet extends lifespan in male rats and Drosophila

Wednesday, March 13, 2024

Foie Gras (1) Peroxisomes

Fasting induces hepatic lipid accumulation by stimulating peroxisomal dicarboxylic acid oxidation

How to deal with oxygen radicals stemming from mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation

Ultimately, when the liver cells are flooded with FFAs the peroxisomes respond* by producing DCAs, di-carboxylic acids. This is basically taking a FFA such as palmitic acid and sticking, by a specific process, a second carboxyl group on to the omega end. This is used a signal to increase peroxisomal oxidation to offload calories without generating the high delta psi which would damage mitochondria. Shortening DCAs ends up with the dicarboxylic acid succinate (HOOC.CH2.CH2.COOH) which is exported to mitochondria where it increases the NADH:NAD+ ratio resulting in the generation of inhibitory metabolites which divert FFAs from beta oxidation to stored triglycerides, fatty liver.

Sunday, March 10, 2024

Foie gras from safflower oil hiatus

Tucker discussed a paper in some detail here on his substack. I fell for it hook line and sinker. It's been pulling me around for weeks. How badly? I've had a copy of Gold's book The Deep Hot Biosphere since late February and I'm only on page 10.

Here's the paper:

Fat Quality Influences the Obesogenic Effect of High Fat Diets

I *think* I understand what is going on but am not quite certain enough to hit "publish" of the third version of my blog post about it. I have been back through so many layers of references that some interesting studies have come up and I think I'll write about one of these next while I continue to mull over the fatty livers. I'm not in an "ignore the blog" phase. It's just the study which has me hooked is very, very complicated and, to me, very, very unexpected. So I can't leave it alone.

More when I can.

Peter

Wednesday, February 21, 2024

Electrochemistry (2) Superoxide

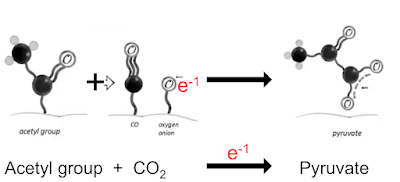

Here's a simplified version of their Figure 1 which is the basic reaction. An electron from the H2O2 attacks the alpha carbon of the pyruvate to give the completely unstable 2-hydroperoxy-2-hydroxypropanoate which spontaneously degrades to acetate and CO2:

"The reaction of pyruvate and H2O2 produces acetate, carbon dioxide (CO2) and water; its transition intermediate has been recently confirmed..."

in which CO2 accepts a geochemical derived electron to become a bound CO molecule and a bound oxygen anion. This lets us re write this line

We can do the exact opposite and convert pyruvate to acetate and CO2, again using a donated electron, this time from H2O2.

"The significance of KG [alpha ketoglutarate], a metabolite that can detoxify H2O2 and O2- with the concomitant formation of succinate in this process is also discussed."

"We have shown that malonate can be formed from oxaloacetate by chemical conversion under the influence of hydrogen peroxide..."

The ROS in this paper which convert oxaloacetate to malonate appears to come from the pyruvate carboxylase enzyme. This is their previous paper which they cited above:

"However, in vitro treatment of oxaloacetate and pyruvate confirm that these conversions are in fact induced by hydrogen peroxide as shown in Figure S4."

"In addition, previous reports have established that ROS mediate the non-enzymatic conversions including that of α-ketoglutarate into succinate [24]-[26]."

This is the alpha-ketoglucarate paper:

Nonezymatic formation of succinate in mitochondria under oxidative stress

"The occurrence of nonenzymatic oxidation of KGL in mitochondria was established by an increase in the CO2 and succinate levels in the presence of the oxidants and inhibitors of enzymatic oxidation. H2O2 and menadione as an inductor of reactive oxygen species (ROS) caused the formation of CO2 in the presence of sodium azide and the production of succinate, fumarate, and malate in the presence of rotenone. These substrates were also formed from KGL when mitochondria were incubated with tert-BuOOH at concentrations that completely inhibit KGDH. The nonenzymatic oxidation of KGL can support the TCA cycle under oxidative stress..."

Wednesday, January 31, 2024

Electrochemistry

A Survival Guide for the "Electro-curious"

Sunday, January 28, 2024

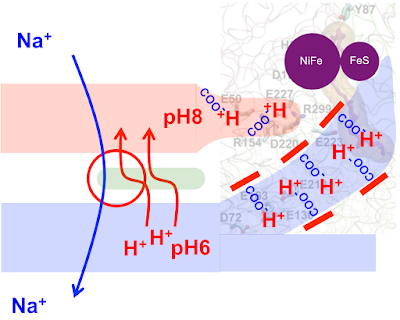

Life (40) Proton pumping

As the protocell membrane becomes progressively more impermeable to both H+ and OH- then running a Na+/H+ antiporter becomes progressively more difficult. At the same time this makes proton pumping potentially advantageous. This is how I am guessing that proton pumping may have developed.